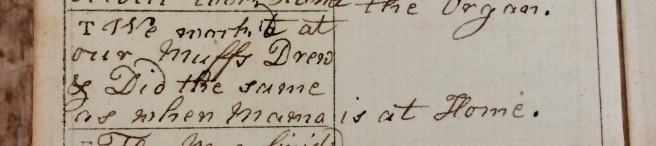

On Thursday January 4th 1776 Susanna wrote:

“We worked at our muffs, drew and did the same as when Mama is at home”.

Beyond making muffs and drawing, Susannah doesn’t list the activities that comprise what they do “when Mama is at home” but Mama (her Stepmother) presumably oversaw Susannah and Lucy’s education taking on teaching the girls what they needed to know. And what they needed to know was how to write, how to read in order to study the Bible and other suitably improving books, plus some arithmetic so that, as they got older, they would be able to record their own as well as the household expenses.

Girls of her social level would also be taught other accomplishments such as needlework, music, drawing and dancing. Apart from these, fresh air and exercise were part of their daily activity and, luckily for them, there seem to have been a number of games to be played and entertainments to be enjoyed as well (all covered in next post). It may also be that what they did when Mama was at home was part of a daily morning routine (like going to school – why bother to mention it?) and the exciting part of the day was later on: visiting and taking tea with friends and cousins.

Writing:

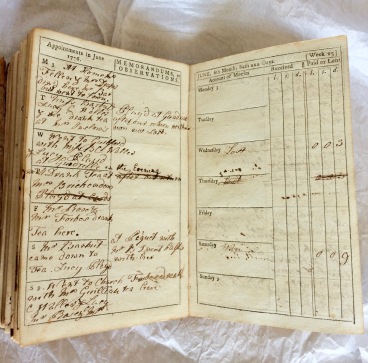

Susannah’s diary entries show that their father valued their education as by the age of 14, she had been taught how to read, how to write and how to do maths. Susannah’s handwriting is generally wonderfully neat although there are weeks when her writing gets messier – I suspect that she sometimes wrote the diary the following week so was trying to remember what had happened – causing some crossings out and smudges! Her spelling is excellent – though she sometimes struggled with surnames as there are various spellings for the same people e.g. Mr Hage and Mr Hauge who presumably is in fact Mr Hague.

Reading:

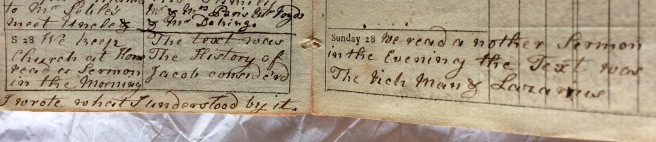

Susannah noted that on Sundays when they didn’t go to church, they read sermons instead, or Mama read a sermon to them. On Sunday January 28th 1776 she wrote,

“We keep Church at home. Read a sermon in the morning. The text was “The History of Jacob Consider’d”. I wrote what I understood by it. We read another sermon in the evening. The text was “The Rich Man and Lazarus”.

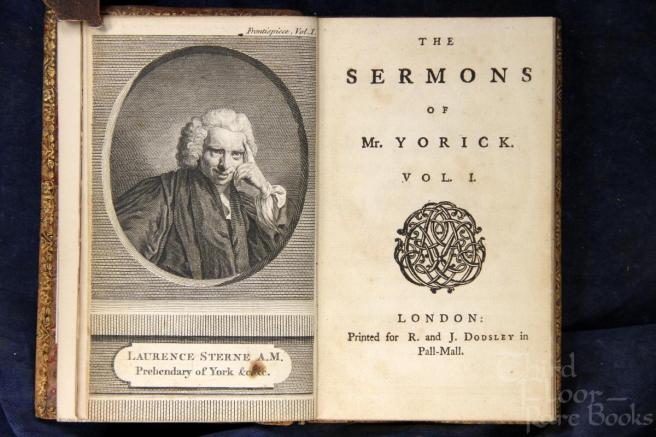

There seems to be a slightly laboured tone in “I wrote what I understood about it” which is hardly surprising as, having noticed that her references to sermons seemed to be very specific, I searched online for the sermon they read on Sunday January 7th 1776 which she calls “Felix’s behaviour towards Paul explained”, and quickly found that they were reading from a volume of Laurence Sterne’s “Sermons of Mr Yorick”. On other Sundays, as well as going to church, they cover Sterne’s sermons on The Prodigal Son, The Rich Man and Lazarus, Pride, Humility and The Advantages of Christianity to the World and again Susannah wrote on a couple of Sundays, “I wrote what I understood of it“.

Laurence Sterne, now more famous as the author of the novels Tristram Shandy and A Sentimental Journey was very well-known at the time for his sermons. Having myself read “Felix’s behaviour towards Paul explained”, I can state with some authority that it is not a light or easy read!

The Huguenot’s Protestant faith would have followed the tenets of John Calvin, believing in salvation through individual faith without the need for the intercession of a church hierarchy (unlike the Roman Catholic church) and on the belief in each person’s right to interpret scriptures for themselves, and this would have been in tune with Laurence Sterne’s Latitudinarian theology (see link for definition). By Susannah’s day, she and her family attended the local Anglican parish churches although her parents and grandparents were baptised, married and buried at the French churches in London, established following the Huguenot influx of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. For example, her father was baptised at the French Artillery Church in Spitalfields in 1726 and returned to his Huguenot refugee roots to be buried in 1808 in Christchurch, Spitalfields.

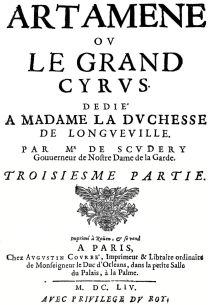

Susannah wrote down the titles of two other books: firstly, she noted twice that Mama read to them from a book she calls “Cyrus”. Cyrus, I have deduced, refers to a hugely popular French novel published in 10 volumes at the end of the 17th century as Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus written by Mademoiselle de Scudéry.

The book is considered the original Roman à Clef and is loosely based on classical figures and classical tales. The 10 volumes amounted to around 1,954,300 words but presumably they just dipped into it!

On Thursday 2nd February, Susannah says “Lucy read Les Journes Amusant” and I picture Lucy reading it out loud to her sister.

This will be Madame de Gomez’s Les Journées Amusantes (the amusing days) which was another huge European bestseller in the early 18th Century. An English version by Eliza Haywood was available soon after the volumes were published, but as Susannah writes the title in French, I think they must have been reading this and Cyrus in the original French. As they travelled to France later in the year and Susannah then wrote her entries in French, 90 years on from her Great Grandfather’s arrival in London, their French heritage must still have been of great importance to this Huguenot family.

Arithmetic:

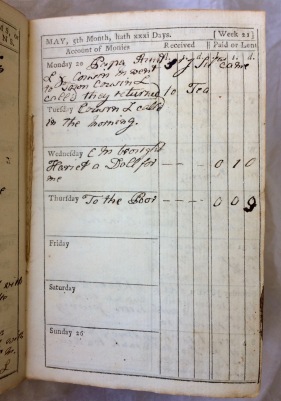

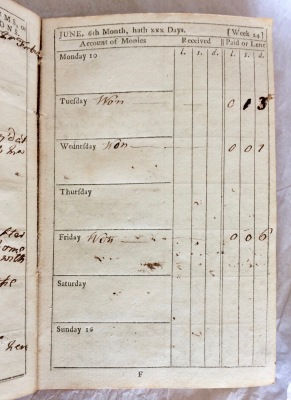

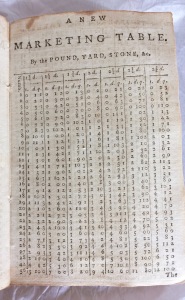

(c) M. Nairne 2017

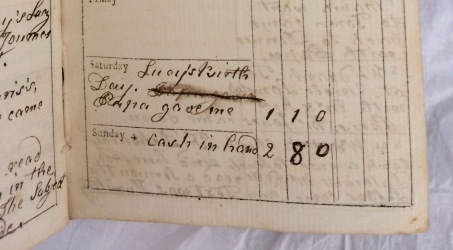

At the end of The Ladies Annual Journal or Complete Pocket Book for the year 1776 there are Tables of numbers for help in accounting which seem quite complicated to me in our age of the calculator! Also, on each diary page the right hand side is devoted to “Account of monies” with columns for noting L S D (Pounds, Shillings and Pence, the LSD standing for Libra, Solidus and Denarius) and money “Received” or money “Paid or Lent”. Susannah was probably encouraged to keep an account of any money that she had and she does occasionally make entries in the right hand side accounts section:

Susannah has £2.80 cash in hand in January. If you put this into an inflation calculator today, this apparently gives her approximately £300 spending power compared to today – I wonder if that can really be true. She does spend some of her money: she writes down when she has given “To a poor woman” several times and she buys presents, such as a doll for Harriet, her little sister.

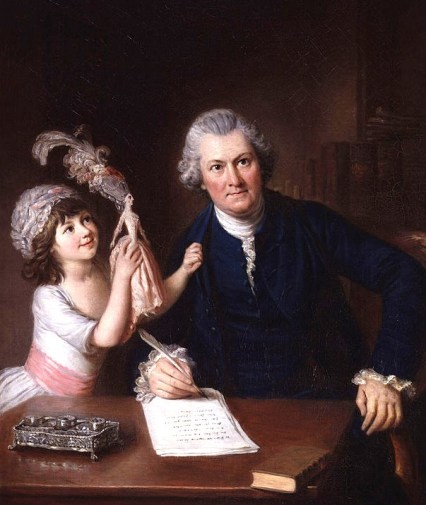

oil on canvas, circa 1775 (c) NPG, London

and, I am sorry to say, she spends money (both winning and losing) gambling in card games (Piquet and Quadrille) in May and June!

I imagine that Susannah’s father encouraged her to write in her diary each day and to start keeping her accounts where she could. He will have been aware that the year 1776 was going to be an eventful one for all of them with moving house, a new baby and a long trip abroad. But, in the longer term, he would also have been keen to ensure that both his two eldest children were educated and accomplished enough to find themselves husbands when the time came and there is no doubt that both Susannah and her sister were very privileged to have such a caring and nurturing father.