In 1776 Susannah Dalbiac was not living in Spitalfields. When she wrote her diary, her family were first living in Bookham in Surrey and then in Wanstead, north east of London. They moved around with surprising frequency but it is exciting to realise that her family still had a strong connection to Spitalfields.

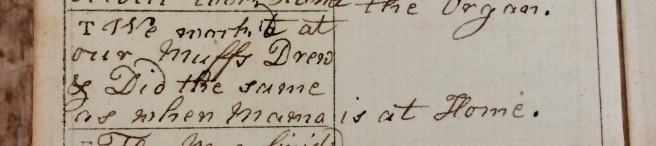

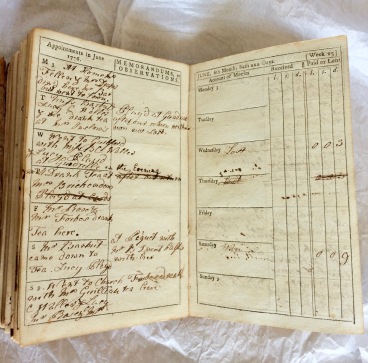

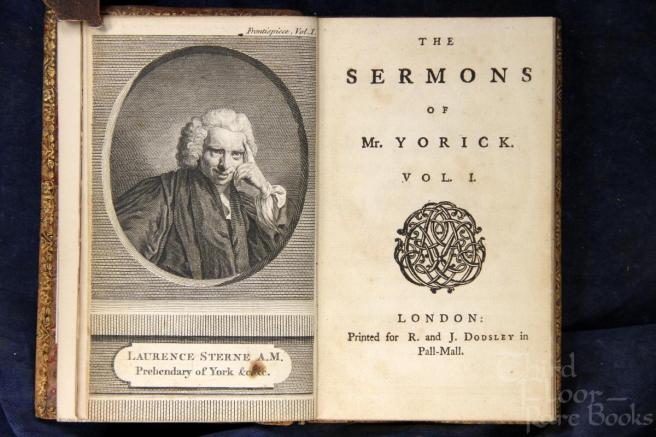

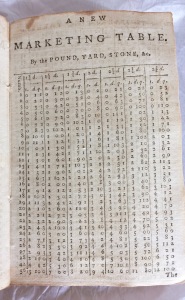

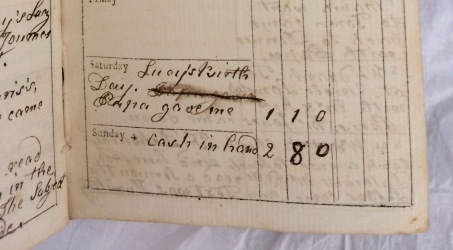

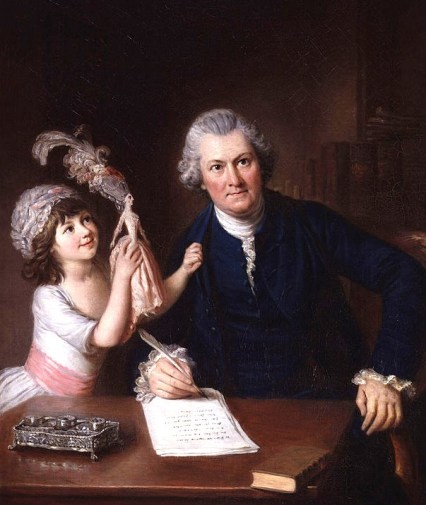

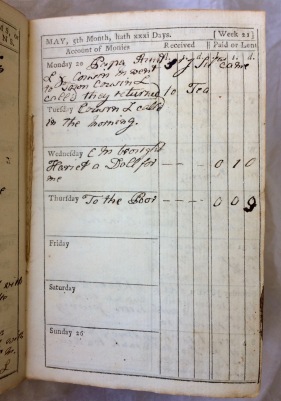

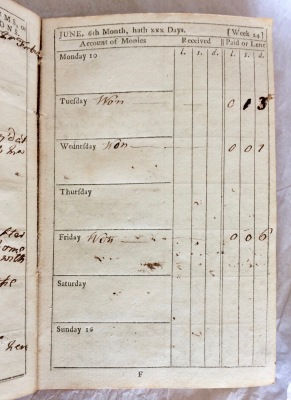

In Natalie Rothstein’s research, The silk industry in London, 1702-1766, Thesis (MA), University of London 1961, a fantastic resource, and now available to read online, she quotes a discussion concerning the controversy over the depression in the weaving industry in the 1760s, where the master weavers’ immense wealth allowed them to own coaches, country seats and liveried servants. The general weaving industry may have been in depression, but this world of master weavers, who were said to “live more like princes” (more like princes than weavers, presumably) would have been Susannah’s corner of this world. Perhaps her Papa and Mama going out in the Phaeton – the Porsche of the day – illustrates their accumulated wealth. See Susannah’s mention of this in the middle of the page here:

And here is a picture of a Phaeton where you can see how elegant a vehicle it was:

From their arrival as refugees in the late 17th century, three generations of Dalbiacs lived in Spitalfields for a span of approximately 100 years . Through the 1700s they occupied No.s 7, 8, 9 and 20 Spital Square (all now demolished), in some of the grandest of the silk weavers’ houses which were built in the early 18th century.

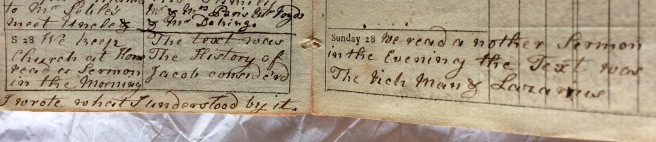

In 1776, Susannah’s uncle, James Dalbiac, and her grandmother, Lucy Dalbiac, were certainly still there and she visited Spital Square a number of times, mentioning staying at her grandmother’s (at No.9) and visiting her uncle (at No. 20). Lucy Dalbiac must have lived in Spital Square for around 50 years by the time she died in April 1776 – one of the last members of an original master weaver refugee family to have lived there continuously – and her Will shows that she left sums of money to 3 local French Huguenot-based charities. On Thursday 29th April 1776, Susannah visits London and notes, “We slept at Grandmama’s & Papa & Mama at Mrs Jourdans.”

The family’s Huguenot refugee story is that, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, two small Protestant Dalbiac boys were smuggled into England hidden in a hamper. From records it appears that one Scipion Dalbiac is the first Dalbiac mentioned as a member of the London weaving industry – in 1698 he is recorded as having “9 looms”. I think Scipion was the father of the two little boys, one also named Scipion and the other named Jacques, and their names were then anglicised: Scipion to Simon and Jaques to James.

As Master Weavers, the Dalbiacs appear to have concentrated on ‘silk and velvet’ and the ‘Black Branch’ of the silk industry, flourishing through the mid-18th century and perhaps doing well when their colleagues languished as the Dalbiacs benefitted from the increase in public mournings and therefore the requirement for mourning dress but also because the black silks were simpler to weave but could still command high prices. Indeed, on Saturday 6th April, 2 days after her Grandmother died, Susannah noted, “Went to town with Papa, Uncle and Aunt Lamotte and Cousin Louise who was so good as to bespeak some mourning for us, Mama not being well enough. “

The Dalbiacs of Spitalfields

[The following is based on the text of family history research undertaken by the late Guy Hatfield, approximately 20 years ago, and kindly passed on to me by the Dalbiac family]

Susanna’s grandfather, James Dalbiac, was admitted to the Weavers Company as a Foreign Master in 1711 on the report of Simon Dalbiac – probably his brother. His first premises were apparently in Brick Lane from which he moved in 1719-20.

We know that James was already living in Spital Square in 1720 for rioting journeymen weavers broke the windows of his house and, indeed, very nearly wrecked it during the great anti-calico campaign of 1719-21. In a period of over seventy years only one other weaver aroused the journeymen to such fury! James Dalbiac was alleged by the journeymen to have said that they were an idle lot who did not want to work (for there was considerable unemployment at the time which was thought by the silk industry as a whole to be due to the increasing use and wear of printed calicoes, a rival cloth). He denied ever having said anything of the sort and, on the contrary, claimed he had subscribed to the costs of the bill to prohibit printed calicoes. Moreover, when everyone thought that the bill was going to become law in 1720, he had raised the wages of his windsters 2d in the £1 for winding silk (1).

The lessons we can deduce from this episode are firstly, that James had prospered greatly since his admission to the Company, for the move from Brick Lane to Spital Square was a distinct social advance. Moreover, he must have had a large and important business for the journeymen weavers to have singled him out and for the Court to have decided to investigate the “riot at Mr Dalbiac’s”. On the other hand, since no-one else provoked the journeymen and no-one else exercised his right to summon a Full Court in the period, let alone present a long justification of his behaviour, one suspects James Dalbiac was a quarrelsome man.

He moved from No.7 to No.20 Spital Square by 1727 to an elegant house illustrated in the Survey of London volume on Spitalfields (2). His standing locally may be deduced from the fact that with the designer and weaver John Vansommer and the mercer Nicholas Jourdain he signed the declaration of Trust for the French Church of the Artillery Ground. He also became a Trustee for the Norton Folgate Court House in 1744. Of his public zeal there is no doubt for he offered one of the largest contingents of men in 1745 to serve against the Young Pretender – 80.

One suspects that the Weavers Company had mixed feelings about him. They did not try to recruit him for the Livery until 1740 and he was never invited to serve on the multifarious committees which dealt with the various economic matters affecting the weaving trades at the time – the import of foreign silks, the use of printed fabrics, the passing of the Manchester Act in 1736 etc. In 1740 the Company resolved that any freeman of the Company whether or not free of the City of London could be elected to the Livery, a device which recruited many not very willing Huguenots and saved the Company’s finances. James Dalbiac was thus recruited.

James appeared before the Court of Assistants in January 1747 to complain bitterly about the drawbacks given on foreign wrought silks and velvets when they were re-exported to the West Indies and other colonies. The vehemence with which he presents his argument suggests that he either exported to the West Indies himself or sold silks for export to that market. To judge from the length of the report, the Court listened to him very carefully. They then asked him for some figures to support his case and for money to support the application to Parliament which he wanted made. As he offered neither, he was asked to go away and produce the figures at a private court as soon as he could do so but, oddly enough, there is nothing further in the Court Books. Perhaps the contribution they also expected deterred him. When he died in 1749, he was described as “an eminent black silk weaver reputed to have died very rich”. (3).

His two sons, James and Charles Dalbiac, advertised from their address in Spital Square from 1749-1778. These two brothers married two sisters: the Gentleman’s Magazine reported the wedding of Mr James Dalbiac junior of Spital Square to a daughter of Mr Peter Devisme of Hamburg, merchant, “with £5000” (4) while in 1759 Charles Dalbiac of Spital Square “Esq” (a term used sparingly at this time) was reported to have married a Miss Devisme of Clapham (5). James and Charles Dalbiac advertised in Mortimer’s Directory of 1763 as weavers of silk and velvet but they must still have continued in their father’s speciality for they signed the earliest surviving trades union agreement (6) in the industry in 1769 in the Black Branch (there was a previous List of Prices agreed in 1763 but not a single copy has been traced). James was a trustee under the local act of 1759 (7). In 1779 the house in Spital Square passed to another owner, presumably signalling the moment when the Dalbiacs finally moved up and away from their original place of refuge.

Another branch of the family also settled in London was headed by Simon Dalbiac, who introduced James to the Weavers Company in 1711. Because of the somewhat conservative habits of the Huguenots when giving Christian names, this Simon was presumably the father of Simon Dalbiac who advertised with him from No.8 Spital Square from 1749-55 and later.

Simon Dalbiac junior offered 25 men in 1745, a respectable offer even if outshone by that made by Captain James Dalbiac. Moreover, their firm bought £218 12s 6d of raw silk on their own account from the Bosanquets in 1759 (8). The smaller firms would have obtained their silk, possibly even ready thrown, through a silkman, while only the more substantial firms under-took all the capital risks themselves. One of the Dalbiac companies ultimately joined forces with a member of the Barbutt family for there is a bill dating from 1771 for bombazine bought by Thomas Fletcher of Stafford from Dalbiac, Barbutt & Co. Barbutt was, incidentally another family associated with the weaving of black silks from earlier in the century. (See Guy Hatfield’s notes below)

In fact, James and Charles dissolved their company in 1780 with James (Susannah’s uncle, now aged 60) continuing with his son, also called James, as there is a printed leaflet announcing:

The Partnership between James Dalbiac and Sons, of Spital-square, Merchants, being dissolved by mutual consent, Notice is hereby given, that the Business will in future be carried on by the said James Dalbiac and James Dalbiac, jun. who are to receive and discharge all Debts owing to and due from the said late Partnership.

Other Spitalfields properties associated with the family:

12 Fournier Street:

Susannah’s older first cousin, Louise Lamotte, who features many times in the diary as CL (Cousin Louise) married the Reverend Benjamin Houssemaine Du Boulay. British History Online records that: “In 1759 and 1766 the house was occupied by the ‘Rev. Mr. Dubeloy’, probably the Benjamin Du Boulay who was a minister of the French Church in Threadneedle Street, and probably Fournier Street, in 1752–65.” He died relatively young, leaving his widow to move back to Wanstead to live either with or near her parents, Mr and Mrs Jean Lagier Lamotte.

37 Spital Square

Susannah mentions Mr Gallie, a surgeon, who lived in 36 or 37 Spital Square, twice in her diary. He visits her stepmother after she has given birth. It is clear from Susannah’s short daily notes that her mother is not completely well after having her baby, and Sir John Silvester, an elderly but eminent doctor, connected to the French Protestant Hospital (La Providence), also visits her a number of times and they all pay a visit his house. It is possible that Susannah’s own mother died in childbirth (at the age of 35) and I imagine that her father was determined to get the best possible medical attention for his young, second wife, to ensure she was in no danger after childbirth.

58 Artillery Lane

This house, with its splendid 18th century shop front, was occupied by the Jourdain family until at least 1772. British History Online relays the following: “Nicholas Jourdain, the lessee of both houses in 1756 and occupant of No. 58, was elected a Director of the French Protestant Hospital of ‘La Providence’ in 1749 and one of the Governors of the Spitalfields workhouse in 1754. In 1755 and 1763 he appears to have had a partner named De Gron, and in 1772 another named Rich. His connexion with No. 58 seems to have ended shortly after 1772, when he was perhaps in financial difficulty as his will, made on 1 September 1784 and proved on 18 July 1785, describes him as formerly of Spitalfields, mercer, but then of Morden College on Blackheath.”

BHL doesn’t mention that Bailey’s Northern Directory has “Dalbiac, Charles, Barbut, and Jourdan, weavers, Spital Square” listed for 1781. They were clearly close friends of Susannah’s father as the Jourdains are mentioned by her a couple of times, once when she says that her parents sleep at “Mrs Jourdain’s” for the night and once when Mr and Mrs Jourdain come for dinner. Could Susannah’s parents have stayed the night at 58 Artillery Lane? It’s a nice thought.